Myths, Reality And Absinthe - The Truth About Thujone

Thujone Facts And Legal Limits

Thujone is present in most species of Artemesia and Artemisia absinthium contributes most to the thujone present in absinthe.

In the UK and the rest of Europe, the maximum permissible limit for thujone is 35 mg/l (or 35 ppm). In the US, the maximum permissible limit for thujone is 10 mg/l (10 ppm). All of our absinthes comply with the European standards for thujone. At the concentrations present in correctly distilled absinthe, whether 'modern' or vintage, thujone is not harmful.

Thujone Effects, Myths, Facts, And Reality

Absinthe has always had an ambivalent history, on one hand it was praised as 'The Green Muse' by its devotees, and on the other it was condemned by it detractors as a cause of madness and moral degeneracy. But is there any scientific or medical basis for either position? Evidence for mind-altering effects and the frequently quoted first-hand descriptions of its mind-altering effects have come from artists and poets who may be expected to describe events in a fanciful manner. Imbibers of alcohol have always described their favourite tipple in extravagant terms, whether it be Burns on whisky or Yeats on wine. The case for its harmful effect is largely based on research on laboratory animals conducted at the behest of the prohibitionist lobby and assumptions drawn from examinations of mental patients in the late 19th century.

The Origins of Absinthe

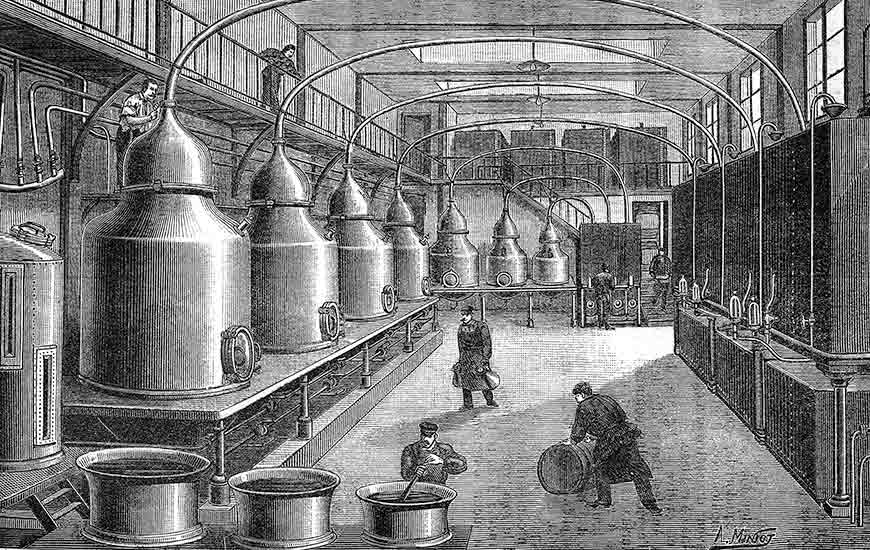

The origins of absinthe can be traced back to the end of the 18th century, when Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor, used wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) together with anise, fennel, hyssop and various other herbs distilled in an alcoholic base as a herbal remedy for his patients. Ordinaire’s recipe eventually found its way into the hands of Henri-Louis Pernod who established the Pernod fils dynasty when he opened his first distillery in 1805, and very soon ‘Extrait d’absinthe’ stopped being a local curiosity and started on its route to becoming a national phenomenon in France, and by the end of the 19th century it had been embraced by the Bourgeoisie and demi-monde alike with over 2 million litres being consumed annually in France.

So what is the published scientific evidence for the harm or benefits of absinthe? Wormwood has had a long history in folk medicine dating back as far as ancient Greece when it was variously prescribed for rheumatism, jaundice, menstrual pains and as an aid in child birth, but it only attracted scientific attention in the mid-19th century. Follow this link if you would like to lear more about wormwood's healing properties.

At this time there was a powerful prohibitionist lobby gaining public attention throughout France and it should be noted that research was rarely totally independent and was conducted to support a particular position, for or against the banning of alcohol. The first published evidence for absinthe’s harmful effects in animals dates from the 1860s (Magnan V. Epilepsie alcoolique; action spéciale de l'absinthe: épilepsie absinthique. Comptus Rendu des Seances et Memoires de la Société de Biologie (Paris) 1869); (Amory R. Experiments and observations on absinthe and absinthism. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 1868). This purpors to show that wormwood oil and alcohol produce a synergistic effect which leads to epileptiform convulsions. Magnan extended his studies to acute alcoholics and concluded that absinthe produced symptoms in humans that were distinct from alcoholic delirium tremens and manifest themselves as epileptic convulsions.

Maximum Concentration of Thujone in Distilled Absinthe

However, it is now accepted that Magnan’s interpretations were oversimplified and alarmist. He not only concluded that absinthe caused medical and psychological troubles not associated with the high consumption of alcohol, he argued that absinthe’s deleterious effects were hereditary. Magnan was preoccupied with the degeneration of the French race, which he blamed on alcohol and in particular, absinthe. There should be no surprise at the correlation of absinthe drinking amongst the destitute and alcoholics, it was the cheapest way of buying strong alcohol. On the other hand, millions of French people enjoyed the occasional glass of absinthe after work without any ill effects. At around the same time, it was becoming generally accepted that thujone, a terpene found in wormwood, was responsible for absinthe’s secondary effects, detrimental or otherwise. It is often stated that the absinthe produced in the 19th century had much larger amounts of thujone present than are allowed in today’s versions of the drink, which have to comply with EU limits of 35 mg/l. Values as high as 260 mg/l have been quoted by Arnold (Absinthe, Arnold WN, Scientific American, 1989).

However analytical techniques available in the 19th century were not capable of separating thujone from many of the related compounds present in the essential oils of the plants used to make absinthe and it is therefore likely that concentrations were just estimated. Indeed, Bedel gives the amount of dried wormwood used in a typical recipe as 2.5 kg in 100 l which, based on widely accepted yields of oil, equates to 87.5 mg/l of oil, of which between 34 and 72% will comprise thujone, giving a final maximum concentration of thujone in the predistilled absinthe of 30 to 63 mg/l assuming 100% extraction (Traite Complet de la Fabrication Des Liqueurs, Bedel, 1899, Paris). However not all of the thujone will find its way into the distillate, and the final concentration in the finished absinthe would have been lower still. This is indeed confirmed when GLC analysis is applied to samples of absinthes and the results do show much lower thujone levels than expected. Analyses were performed on a sample of vintage Pernod fils circa 1900, a sample of absinthe produced by a home distiller and two modern commercial absinthes produced by traditional methods in Pontarlier, France by using 19th century protocols. The vintage Pernod absinthe is shown to have the lowest concentration of total thujone of any of the samples tested and the highest is found in the Swiss sample.

Absinthe And Thujone Effects

The convulsive ED50 of thujone in rats is 35.5 mg/kg/day, and the 'no effect' level is 12.5 mg/kg/day (Margaria, 1963, Acute and sub-acute toxicity study on thujone. Unpublished report of Istito di Fisiologia, Università di Milano). No toxicity studies have been conducted in humans but the FDAs accepts a safe level for food additives as a highly conservative 100 times less than the no effect level in animals. Thus a safe (no effect) dose of thujone could be extrapolated as 8.75 mg/day for a 70 kg human and it can be seen that even at the highest concentrations found in any of the samples tested, the effects of the alcohol would far outweigh those of the thujone. It is therefore very clear that absinthe available in the US cannot have any effects at all with thujone levels kept below the maximum permissible limits of 10 mg/l (10 ppm) and way below the safe, no effect dose.

Can Absinthe Kill or Harm You?

What is more likely to have caused harm to regular absinthe drinkers is the adulterants used in the cheaper varieties. Absinthe existed and still exists in a quality pyramid much as wine does today, for each quality brand there were many more indifferent and positively harmful versions being sold cheaply to those who could not afford to buy a reputable brand. Common adulterants were cupric acetate (to provide the valued green colour) and antimony trichloride (which provided a cloudiness when water was added in imitation of the milky appearance of diluted absinthe). The purity of the base alcohol used for lesser brands would also have been questionable, and toxic levels of methanol from poor rectification would have been a real possibility. An additional aggravating factor is that as the cheaper brands were lower in alcohol than the quality brands, around 45% abv for 'absinthe demi-fine' compared to 68 or 72% for 'absinthe superior', someone drinking the cheaper version and seeking to obtain the same effect from the alcohol would have needed to consume more of the absinthe and hence more adulterants.

Similarities Between Absinthe And Marijuana

On the other hand the base alcohol used in quality absinthe was rectified wine alcohol at 85% which was free from congeners, and although bottled at approximately 70% (to preserve the natural green colour of the chlorophyll) the final absinthe strength when diluted was no more than a glass of wine. Interest in absinthe naturally waned after the ban in Switzerland and France, and scientific interest faded until a paper was published in 1975 (Castillo et al; Nature, 1975) which suggested similarities between the reported effects of absinthe and those of marijuana (Cannabis sativa) and attempted to explain these by highlighting similarities in the molecular geometry of thujone and tetrahydrocannabinol. This reignited the controversy surrounding absinthe but no further evidence to support these findings and in 1999 Meschler and Howlett determined that thujone had no activity at the cannabinoid receptor. (Meschler and Howlett, Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 1999) and current research points to it being a GABA-A modulator (Mold et al, PNAS, 1999). Thujone’s GABA modulating activity explains its convulsant effects at high doses and smaller doses may produce stimulant action (there is an evidence that drinking absinthe produces a clarity of thought that is not usually associated with alcoholic drinks). GABA is a neurotransmitter and primary inhibitor of your central nervous system (CNS). With higher, increased levels of GABA in your brain, excitability decreases and as a result, you become more relaxed.

Absinthe, Wormwood And Health Benefits

So if the case for the harmful effects of absinthe is flimsy, does it have any beneficial ones? Ordinaire first prescribed it as a general tonic but it is doubtful whether he performed any objective research into whether it was improving the condition of his patients, they kept coming back for more so it must be doing them good. The producers unashamedly sold absinthe on the basis of its health giving properties, especially in the years leading up to the ban. In 1844 absinthe was issued to French legionnaires fighting in Algeria as it was believed to prevent fever and kill bacteria in water. Although there were no studies to support this at the time, in 1975 researchers found that dilute oil of wormwood did inhibit the growth of 4 out of 7 types of bacteria. (Kaul VK; Nigam SS; Dhar KL. Antimicrobial activities of the essential oils of Artemisia absinthium linn, Artemisia vestita wall' and Artemisia vulgaris Linn, Indian Journal of Pharmacy, 1976). Wormwood has also been shown to be a hepatoprotective. Gilani and Janbaz found that an extract of Artemisia absinthium protected against acetaminophen and carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. The presence of antioxidants and calcium-channel blockers in wormwood also probably contributes to its hepatoprotective effects. (Gilani AH; Janbaz KH., Preventative and curative effects of Artemisia absinthium on acetaminophen and CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity, Gen. Pharmacol, 1995; Gilani AH. Search for new calcium channel blocking drugs from indigenous plants, International Congress on Natural Products Research, 1994, August 1-5, Halifax). Recent studies have demonstrated that extracts of wormwood (and other plants used in absinthe) have CNS cholinergic receptor binding activity and therefore contrary to accepted wisdom, absinthe may actually improve cognitive function (Wake et al, J Ethnopharmacol, 2000 Feb).

Absinthe, Distilled Aniseed Spirits, And Hallucination

In conclusion, there is no scientific evidence that absinthe ever contained the high concentrations of thujone that would have led to detrimental effects or that it has hallucinogenic or mind altering properties. The health problems experienced by chronic users were likely to have been caused by adulterants in inferior brands and by the high levels of alcohol present. Claims for beneficial effects must also be treated with some scepticism as again, the detrimental effects of the alcohol would presumably outweigh any benefits. It seems likely that the phenomenal success of absinthe during the 19th century was due to one factor, the French love of aniseed drinks, opium was pretty popular too in France, hence the hallucinations when combined with spirits that were 140 proof. The modern equivalent of absinthe, pastis, is by far the most popular distilled spirit in France with 125 million litres being consumed annually. Perhaps the reason that so much absinthe was consumed, and absintheurs waxed so lyrically about it was simply because it tasted so damn good.

This original article first appeared in Current Drug Discovery, September, 2002